Early years

Early years

Eleanor was born on 21 June 1802, the eldest child of William and Eleanor Evans,

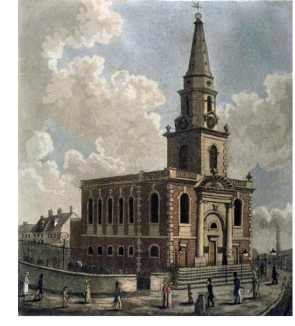

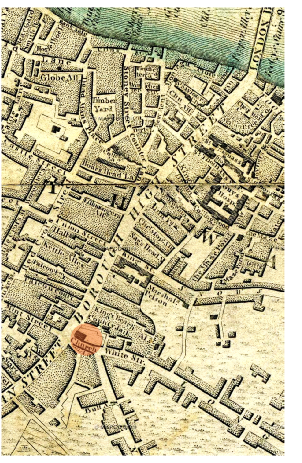

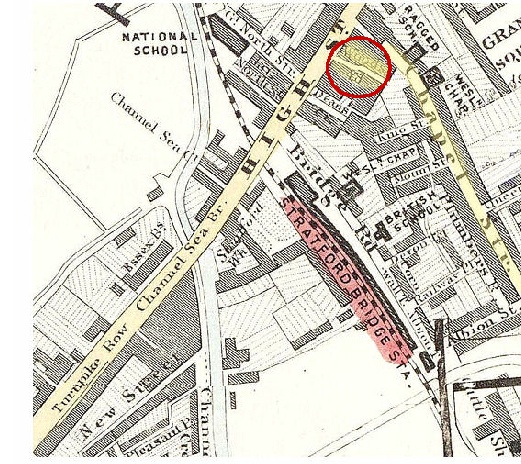

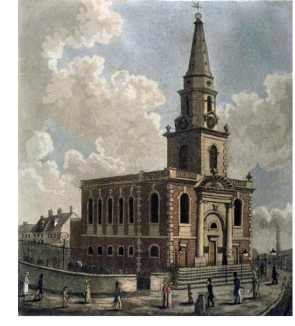

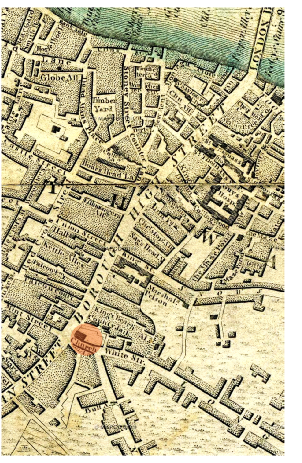

and was baptised a few weeks later at the Church of St George the Martyr. The Church

(shown in the illustration on the right and marked on the map of 1804) stands at

the intersection of Borough High Street and Great Dover Street in Southwark in south

London. In the three centuries before Eleanor’s birth, the area was notable for two

things: prisons and taverns.  Five of London’s eighteen prisons were located in Southwark,

including the famous Marshalsea and Clink prisons, which were only a few streets

from the Church. As famous as its prisons was its inns. Borough High Street was the

main thoroughfare to London Bridges and, as such, was an entry point to London from

Portsmouth in the south and Dover in the southeast. The High Street was characterised

by its many coaching inns and taverns, many of which were ancient establishments

such as The Tabard Inn (the meeting place of the pilgrims in Chaucer’s Canterbury

Tales) and the George and Dragon which was frequented by William Shakespeare and

referred to in Dickens’ novel, Little Dorritt.

Five of London’s eighteen prisons were located in Southwark,

including the famous Marshalsea and Clink prisons, which were only a few streets

from the Church. As famous as its prisons was its inns. Borough High Street was the

main thoroughfare to London Bridges and, as such, was an entry point to London from

Portsmouth in the south and Dover in the southeast. The High Street was characterised

by its many coaching inns and taverns, many of which were ancient establishments

such as The Tabard Inn (the meeting place of the pilgrims in Chaucer’s Canterbury

Tales) and the George and Dragon which was frequented by William Shakespeare and

referred to in Dickens’ novel, Little Dorritt.

At the time of Eleanor’s birth, her father was described using the somewhat vague

term of ‘labourer’, an occupation which encompassed a variety of jobs. In about 1803,

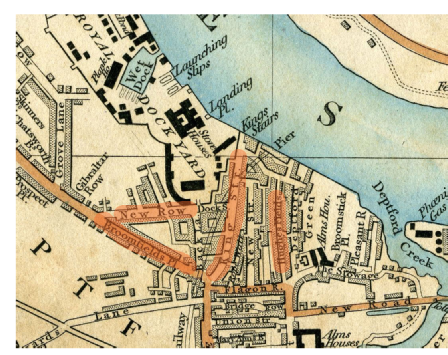

her parents moved from Borough, a few miles east to Deptford. It was here that Eleanor

and her five siblings grew up. In 1803, when the infant Eleanor and her family arrived

in Deptford, it was a thriving area of trade and industry and, until she was in her

early teens at least, Eleanor grew up amidst the bustle of the docks with the smell

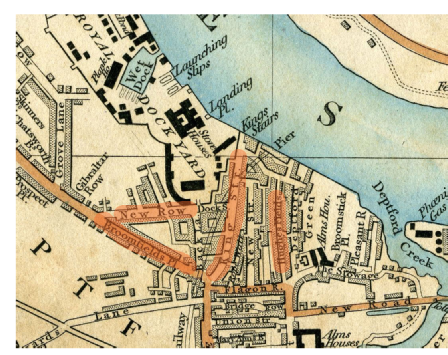

of fresh sawn timber and tar in the air. The map below shows four of the streets

where Eleanor lived between 1804 and 1813.

T he next chapter

he next chapter

Little is know about Eleanor until the 1830s; in 1851, she described herself as a

tailoress, but there is no evidence to suggest she followed this occupation earlier

in life. By 1836, she had met a tailor called George Moss. Their son was born on

30 June 1837 whilst George and Eleanor were living above one of the shops that lined

the Broadway, the bustling thoroughfare a little further south of river. However,

the 1841 census (taken on 6 June) records two other children in the household: Eleanor

Moss born in about 1831 and Emma Moss born around 1833. No baptism records have been

found for Eleanor and Emma (under either the surname Moss or Evans). George may have

been their father, but there is nothing to prove or disprove it.

Only a few months after his birth, in the Winter of 1837, the infant George died.

Not long after his death, two events occurred: Eleanor discovered that she was pregnant,

and George and Eleanor moved from Deptford to Stratford in Essex. Historical evidence

doesn’t show which event came first: perhaps the death of their son, George, was

the impetus they had needed to move, or perhaps the discovery that she was pregnant

prompted George and Eleanor to find a better place to raise their children. Whatever

the order of events, Eleanor was living at New Street in Stratford when she gave

birth to a second son on 23 November 1838. It took until 1868 for his name to be

entered into the baptism register ‘by sworn affidavit’ of the Church of All Saints

in West Ham.

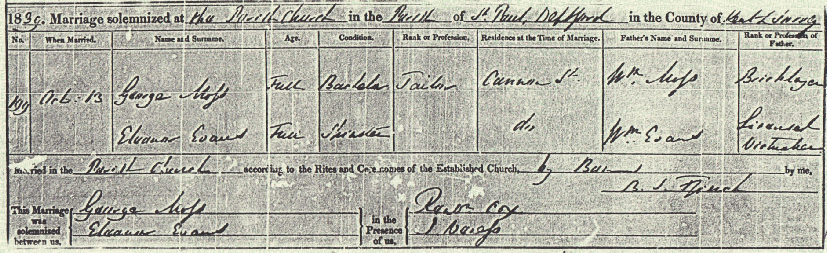

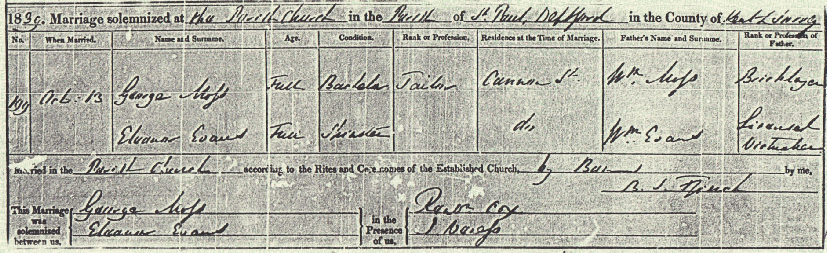

It appears that George and Eleanor were rather lax with church formalities. It was

not until 13 October 1839 that Eleanor and William finally decided to wed. Having

waited so long, they made sure it was a family affair, returning to Deptford and

the Church of St Paul to be married. Eleanor was thirty seven and had borne four

children, but the marriage entry in the parish register (shown below) gives no clue

as to why she and George had waited so long.

Hard Times

After their marriage, Eleanor and her family returned to Stratford, where Eleanor

gave birth to at least three more children: Rosetta (May 1841), William (1843) and

Eliza (1845). If the family had moved to Stratford in search of work and a better

life, they were disappointed. The middle years of the nineteenth century were difficult

ones for many trades and wages declined in real terms. In 1851, Eleanor described

her occupation as a tailoress, indicating that she had taken up her needled to assist

her husband to make ends meet.

The death of Eleanor’s husband, G eorge, sometime between 1851 and 1861, and the loss

of his income, left Eleanor, and her children who still remained at home (William

and Eliza), in financial difficulty, but the family managed to make ends meet. However,

by 1865, all of Eleanor’s children had left home and families of their own to support.

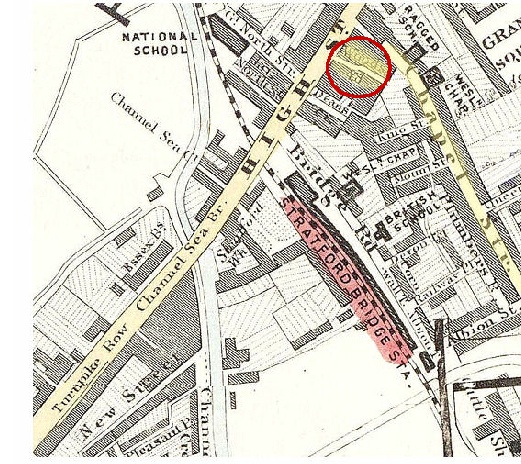

Eleanor moved to 75 Chapel Street (highlighted in yellow on the map on the right)

where she rented a room from a blacksmith and his family.

eorge, sometime between 1851 and 1861, and the loss

of his income, left Eleanor, and her children who still remained at home (William

and Eliza), in financial difficulty, but the family managed to make ends meet. However,

by 1865, all of Eleanor’s children had left home and families of their own to support.

Eleanor moved to 75 Chapel Street (highlighted in yellow on the map on the right)

where she rented a room from a blacksmith and his family.

By the 1870s she found it increasingly difficult to earn her living with her needle:

not only was her hand less steady and her eyesight less sharp, the widespread introduction

of the mechanised sewing machine had reduced the demand for needlewomen. As her circumstances

reduced, so did her living conditions. Her next move was only a step away from destitution

and the workhouse. Wood’s Yard (circled in red) was one of a number of courts and

alleys leading off of the High Street. Its ten hovels had been built in the early

nineteenth century and probably consisted of a brick basement with one or two weather-boarded

living rooms above; along with Dean’s Court and Channelsea Court, it was one of the

slums singled out for reprobation in a report of 1855 which looked at public health

and sanitation in West Ham. Of neighbouring Channelsea Court, the report noted:

“The inhabitants have no water except from the filthy river. Little back yards with

stinking privies. Cholera was very bad here. There is a drain running from the Forest-gate

district past the Stratford station of the Eastern Counties Railway. At that point

it is on the company’s land and partly covered. The open area is very bad … it takes

privy drainage and empties itself into the Channelsea river at a point above where

the inhabitants of the Rabbit-hutch row, and the Channelsea-court dip for their water”.

Woods Yard was little better. As well as the unsanitary conditions, the house was

cold and damp. Even so, Eleanor lived there for at least nine years, finally dying

on 10 May 1890 of bronchitis, at the remarkable age of 88.

Woods Yard was little better. As well as the unsanitary conditions, the house was

cold and damp. Even so, Eleanor lived there for at least nine years, finally dying

on 10 May 1890 of bronchitis, at the remarkable age of 88.

Early years

Early years Five of London’s eighteen prisons were located in Southwark,

including the famous Marshalsea and Clink prisons, which were only a few streets

from the Church. As famous as its prisons was its inns. Borough High Street was the

main thoroughfare to London Bridges and, as such, was an entry point to London from

Portsmouth in the south and Dover in the southeast. The High Street was characterised

by its many coaching inns and taverns, many of which were ancient establishments

such as The Tabard Inn (the meeting place of the pilgrims in Chaucer’s

Five of London’s eighteen prisons were located in Southwark,

including the famous Marshalsea and Clink prisons, which were only a few streets

from the Church. As famous as its prisons was its inns. Borough High Street was the

main thoroughfare to London Bridges and, as such, was an entry point to London from

Portsmouth in the south and Dover in the southeast. The High Street was characterised

by its many coaching inns and taverns, many of which were ancient establishments

such as The Tabard Inn (the meeting place of the pilgrims in Chaucer’s  he next chapter

he next chapter

eorge, sometime between 1851 and 1861, and the loss

of his income, left Eleanor, and her children who still remained at home (William

and Eliza), in financial difficulty, but the family managed to make ends meet. However,

by 1865, all of Eleanor’s children had left home and families of their own to support.

Eleanor moved to 75 Chapel Street (highlighted in yellow on the map on the right)

where she rented a room from a blacksmith and his family.

eorge, sometime between 1851 and 1861, and the loss

of his income, left Eleanor, and her children who still remained at home (William

and Eliza), in financial difficulty, but the family managed to make ends meet. However,

by 1865, all of Eleanor’s children had left home and families of their own to support.

Eleanor moved to 75 Chapel Street (highlighted in yellow on the map on the right)

where she rented a room from a blacksmith and his family.  Woods Yard was little better. As well as the unsanitary conditions, the house was

cold and damp. Even so, Eleanor lived there for at least nine years, finally dying

on 10 May 1890 of bronchitis, at the remarkable age of 88.

Woods Yard was little better. As well as the unsanitary conditions, the house was

cold and damp. Even so, Eleanor lived there for at least nine years, finally dying

on 10 May 1890 of bronchitis, at the remarkable age of 88.